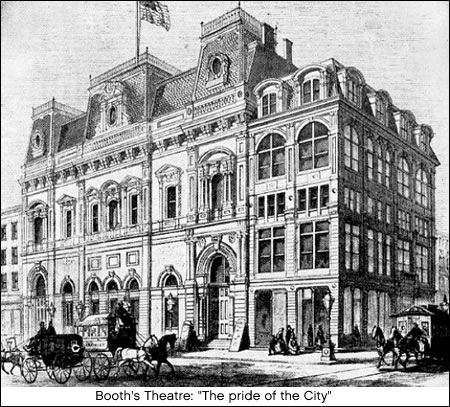

Booth Theatre (NYC)

When 23rd Street Was the Heart of New York's Theatre District

FROM HIS PERCH 20 FEET ABOVE THE SIDEWALK AT THE CORNER

of Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street, William Shakespeare stares impassively at the multitudes below.

The Bard is unnoticed by all but a few, but once upon a time, this corner was his turf.

His bust is mounted on the Sixth Avenue facade of the Caroline, an apartment building

that now occupies the site of Booth's Theatre, once the most important venue in

New York City for the production of Shakespeare's plays and, for a time, the

best-known playhouse in the Flatiron district.

![]()